Febrary 5, 2020 - Barbara Vonarburg, NCCR PlanetS

Uranus and Neptune are the outermost planets of our solar system. In terms of their size, composition and distance from the sun, they are similar and clearly differ from the inner terrestrial planets and the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. “However, there are also striking differences between the two planets that require explanation,” says Christian Reinhardt, who studied Uranus and Neptune together with Alice Chau, Joachim Stadel and Ravit Helled, all PlanetS members working at the Institute for Computational Science of the University of Zurich. “For example, Uranus and its major satellites are tilted about 97 degrees into the solar plane, and the planet effectively rotates retrograde with respect to the sun,” explains Joachim Stadel.

Furthermore, the satellite systems are different. Uranus’ major satellites are on regular orbits and tilted with the planet, which suggests that they formed from a disk, similar to Earth’s moon. Triton instead, Neptune's largest satellite, is very inclined and therefore most likely a captured object. Finally, they could also be very different in terms of heat fluxes and internal structure.

Similar formation – different collisions

“It is often assumed that both planets formed in a similar way,” explains Alice Chau. This would readily explain their very similar masses, mean orbital separation from the sun and possibly composition. But where do the differences come from? Since impacts are common during the formation and early evolution of planetary systems, a giant impact was proposed as the origin of this dichotomy. However, prior work either only investigated impacts on Uranus or was limited due to strong simplifications in the impact calculations.

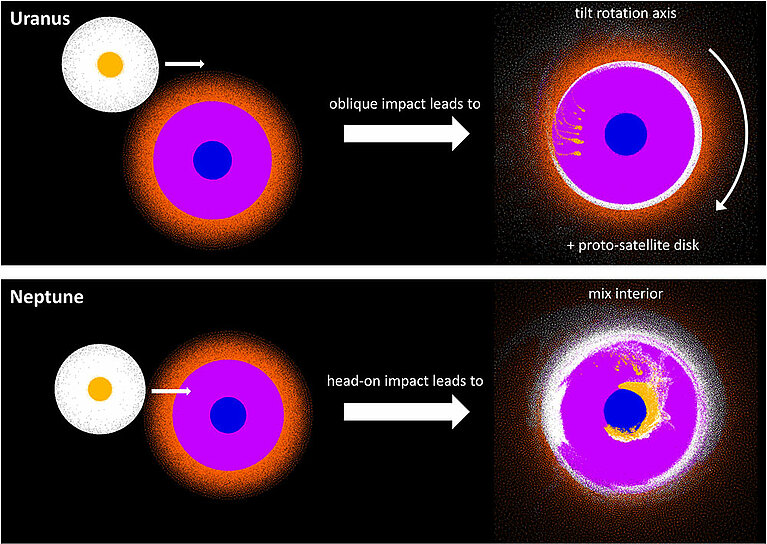

The team of UZH scientists have now for the first time investigated a range of different collisions on both planets using high-resolution computer simulations on CSCS supercomputer "Piz Daint“. Starting with very similar pre-impact Uranus and Neptune, they showed that an impact of a body with one to three Earth masses on both planets could explain this dichotomy. In the case of Uranus, a grazing collision can tilt the planet without affecting the planet’s interior.

On the other hand, a head-on collision for Neptune strongly affects the interior but does not result in the formation of a disk, and is therefore consistent with the absence of large moons on regular orbits. Such a collision, which mixes up the planet’s deep interior, is supported by the larger observed heat flux of Neptune. “We’ve clearly shown that an initially similar formation pathway to Uranus and Neptune can result in the dichotomy observed in the properties of these fascinating outer planets,” concludes Ravit Helled. Future NASA and ESA missions to Uranus and Neptune can provide new key constraints on such a scenario, improve our understanding of the formation of the solar system and provide a better understanding of exo-planets in this mass regime.

The article was first published at UZH news >

(Image on top: Neptune photographed by Voyager 2. - NASA/JPL)

Reference:

Reinhardt C, Chau A, Stadel J & Helled R: Bifurcation in the history of Uranus and Neptune: the role of giant impacts, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, stz3271, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stz3271